Numerical Computation of Linking Number

To implement the above idea in a machine language we can ask ourselves a few important questions. These questions are discussed below one by one.

Should we keep our loops (both red and blue) continuous or should we discretize them?

If we want to keep the loops continuous, then we have to feed the algorithm the exact equations of the loops every time we compute. Two differently deformed unlinks will have different equations, and feeding the exact equations is easier for completely circular loops but becomes immensely difficult for much more complex deformations of the same. Ensuring an input for the algorithm becomes difficult this way, and thus, we should avoid relying on a continuous approach. Well then, how does discretization help in this matter?

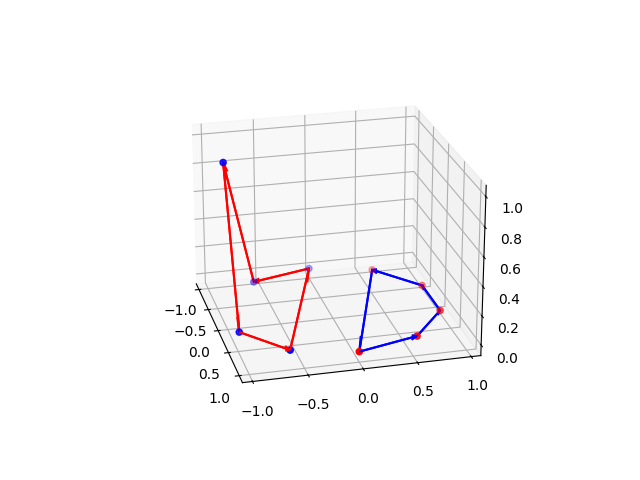

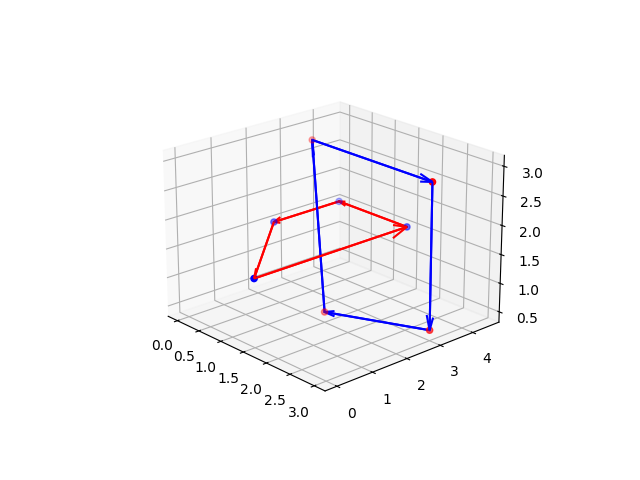

What we mean by discretization of the loop is having a certain number of discrete points (data points) on the continuous loop and then joining each point with a straight line. The Figures below illustrate an example of a discretized unlink and a discretized Hopf link.

How do we obtain the Seifert surface associated with the blue loop?

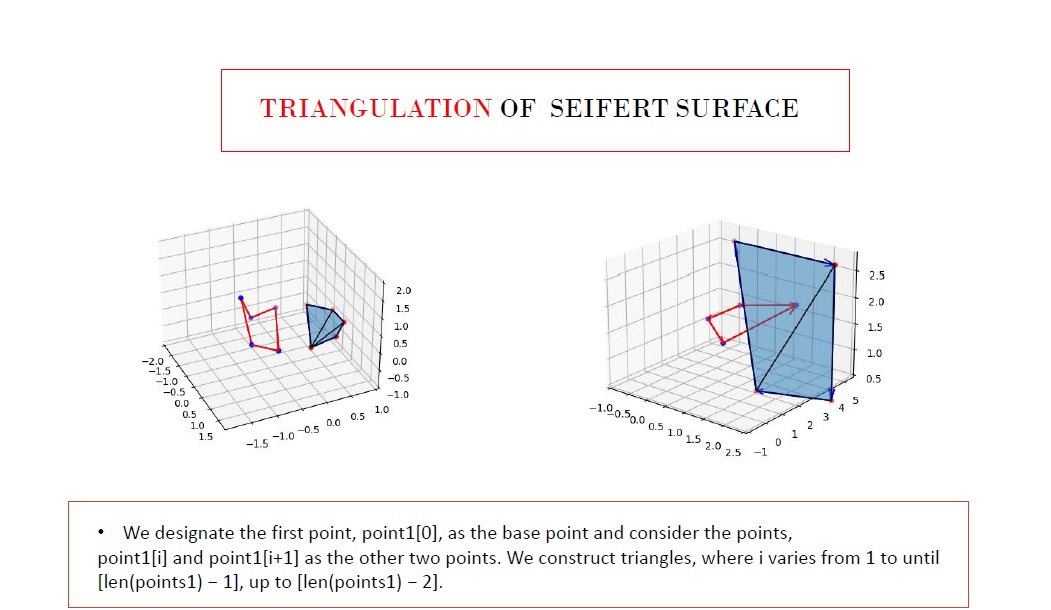

Algorithm 1: Constructing the Seifert Surface of the Blue Loop

1. Initialize an empty list for triangles: triangles = []

2. Loop through points in points1 to create triangles.

3. Create a 3D polygon from triangles using Poly3DCollection.

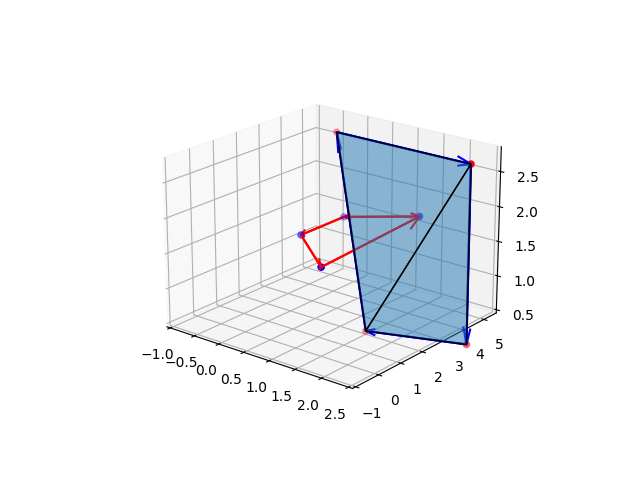

The Seifert surface obtained is not a smooth surface, rather it is a discrete triangulated approximation of the same. An example for the Hopf link is shown below:

Crossing the Seifert surface: top to bottom and bottom to top

Algorithm 2: Barycentric Plane and Line Equations for Finding Crossing Points

1. Compute barycentric line equations for red vectors.

2. Solve line equation for red vectors crossing blue triangles.

How do we compute the linking number for both the links?

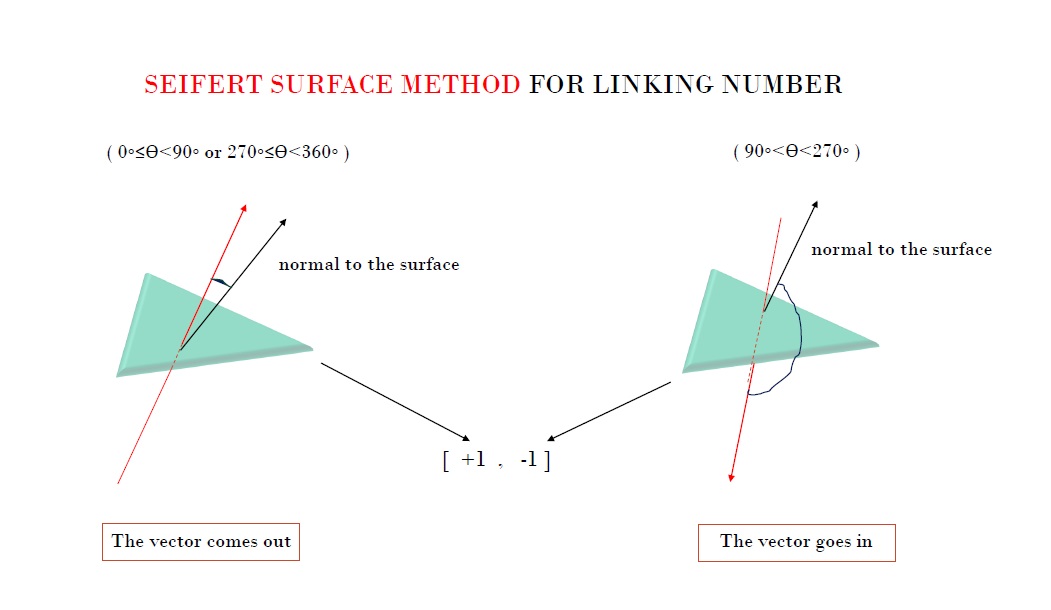

If the crossing is from bottom to top, append +1, and -1 for top to bottom crossings. Sum the values to get the linking number, which is 1 for a Hopf link and 0 for an unlink.

For each triangular surface, the code solves the line equation for all red vectors. If the solution lies inside the triangle, it prints the result; otherwise, it prints "Solution does not exist." This process repeats for all triangular surfaces in a loop to compute crossing points. Vectors lying on the same plane as a triangle, whether inside or outside, are not considered crossing, so the code returns "Solution does not exist" in such cases. Next, we utilize the direction of the gradient vector to the surface at the point of intersection to determine the direction of crossing.

We compute the angle between the normal vector of the Seifert surface and the vector that crosses the Seifert surface to determine if the crossing is positive or negative. This helps in understanding the orientation of the Seifert surface. The angle is calculated using the dot product and normalized vectors, with results printed to show the orientation in the Linking List. If the angle falls within the range [0,90) or (270,360], the red vector is considered to have crossed the surface from the bottom to the top side. Conversely, if the angle is in the range (90,270), the red vector is considered to have crossed the surface from the top to the bottom side. This is how the orientation is determined. The code then prints the value of the angle.